While researching nonverbal communication with an autistic girl named “Hayley”, I realized the pervasive and painful lack of understanding about the nonverbal children discussed in the video above. Many children diagnosed with autism are seriously misunderstood, and spreading the information below could literally save a life. It already has. A nonverbal child was almost denied a heart transplant at Stanford…until he showed he could communicate with a letter board. Here are the most common misconceptions:

- People with autism are often mistakenly thought to be mentally retarded, but they exhibit the full spectrum of IQ. In fact, their average intelligence may be at least 17 percent higher than the general public.

- Autistic people are also assumed to lack empathy. Their writings, however, show that they wonder why we aren’t more empathetic, kind and loving towards them, and towards each other.

- Autistic people are thought to be aloof, and to not form attachments to others, but they write about feeling lonely, and often worry about people they love.

Understanding more about Hayley’s world meant studying the technique she used to learn language, so I attended Rapid Prompt Methodology (RPM) workshops by speech and language pathologist Elizabeth Voseller, and the woman who developed it, Soma Mukhopadhyay, HALO Executive Director of Education.

One participating family told me a dramatic story about RPM and their ten year old autistic son. He developed cardiomyopathy from a viral infection, and needed a heart transplant to survive. A match was found, but he was almost denied this opportunity for life, because Stanford’s transplant team didn’t think he was a proper surgical candidate. They thought his autism meant he couldn’t comply with the rigorous post-op requirements. The boy radically changed how his doctors saw him when he meaningfully expressed himself using RPM. The team immediately approved the surgery. He was still alive when I met him, two years later.

Autistic people are often unfairly judged by what they do, and what they can’t do. They can’t manipulate their facial musculature to speak, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they aren’t understanding what we say. They can’t control their eyes to look at us directly, but that doesn’t mean they don’t see or care about us. They might struggle to type and read, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t thinking deep thoughts. Hayley can repeat short sounds, or scream spontaneously, but she never initiates words. That fits a clinical pattern Elizabeth believes to be fundamentally different from autism. Children like Hayley are labeled nonverbal incorrectly. “Nonverbal” implies they lack language, but their writings demonstrate that they have intact language with all of its components. Their morphology, syntax, semantics, and phonology are the same as ours. They should be referred to as nonvocal. If these children don’t have a primary language disorder, then what’s going on?

Neuropsychiatric symptoms overlap widely and can have multiple causes. We are trained to choose the simplest hypothesis to explain all of our observations. That is how strokes and tumors were accurately located before brain scans were available. Elizabeth knows about the neurology of language and thinks some of these children suffer primarily from apraxias, the lack of understanding how to perform complex behaviors. One example of an apraxia is shoe tying. After a stroke, someone can develop a specific apraxia, losing this knowledge. Some children never acquire it.

Hayley is fairly coordinated now, but she struggles with initiating speech and typing. RPM uses tactile and visual prompts when necessary to get her going. Hayley also has difficulty stopping behaviors, such as her repetitive hand-flapping. People with severe Parkinson’s Disease also exhibit difficulty starting and/or stopping, but their difficulties develop over time and are recognized as motor. Children born with similar difficulties often never get the chance to show us who they can be due to false assumptions.

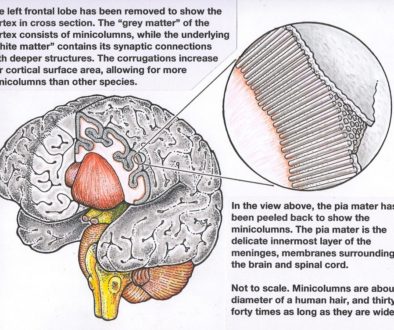

There are many accepted neurological conditions in which the patient can’t speak, but they still understand language. This is because the brain areas involved are entirely separate. The pattern described by Elizabeth might be explained better by a sensory, rather than motor problem. That could be why their behavior looks like both an apraxia, and a dysregulation of beginning and ending movement. Autistic children are known to have problems with sensory integration, which can look just like a motor problem since sensory information directs our movements. The major feedback control loops involved are touch and proprioception (the ability to precisely locate our body in space).

In the 1970s, a UCLA psychologist suggested some children have only a sensory processing problem. Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD) was proposed as a new diagnosis, but it has been a subject of debate ever since. Beginning in 2000, the SPD Foundation spearheaded an intense campaign for recognition of SPD as a diagnosis in the upcoming DSM-5, the American Psychiatric Association’s manual of diagnostic codes. Members included researchers from Harvard, Yale, Duke, MIT, University of Wisconsin-Madison, UCSF and others. The DSM-5 was published on May 27, 2013, excluding SPD because they found “inadequate evidence.” Insurance companies will deny payment for any therapy, even an effective one, if a diagnosis is not in the DSM.

The same year DSM-5 was released, dramatic evidence for SPD as a separate diagnosis was published by Elysa Marco, MD, a cognitive and behavioral child neurologist at UCSF, and her Postdoctoral Fellow Julia Owen, PhD. They found correlations between their clinical evidence for SPD and very specific white matter abnormalities in the brain areas associated with sensory processing. Psychiatrists continue to lump all non-speaking children with repetitive behaviors together. Countless children are currently labeled as autistic spectrum disorder. Many can’t sit still for neuroimaging that might challenge this diagnosis.

The Medical Director of the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH), Thomas Insel, MD, declared the DSM-5 to be invalid when he said, “The weakness” of the manual, “is its lack of validity.” “Unlike our definitions of ischemic heart disease, lymphoma, or AIDS, the DSM diagnoses are based on a consensus about clusters of clinical symptoms, not any objective laboratory measure.” The NIMH funds the majority of research on mental health and he said he wouldn’t fund research based on DSM-5 diagnoses. You can read about it here.

When I realized that all of Hayley’s overt behaviors could be explained by this new hypothesis, it was very eye-opening… and has major ramifications. One of Elizabeth’s missions is to teach RPM to people who work with non-speaking autistic children, because it gives children with poor body control a critically-needed voice. Some autistic behavior could be from frustration at being misunderstood, and trapped in a body that doesn’t function like ours. If a child doesn’t actually have a language problem, forcing them to practice simple phrases like “See Spot run” over and over must be torture. It would be for me. Their frequent temper tantrums become understandable.

These children take in and process far more than we realize. They write about feeling humiliated, frustrated, angry, and hurt by what people say in their presence. Parents have a variety of reactions when they realize their child is socially aware and can understand language… ranging from relief that they can now communicate, to regret and horror that they didn’t find out sooner. Not being able to speak can actually be the opposite of having nothing to say. That’s why I’m spreading their words…